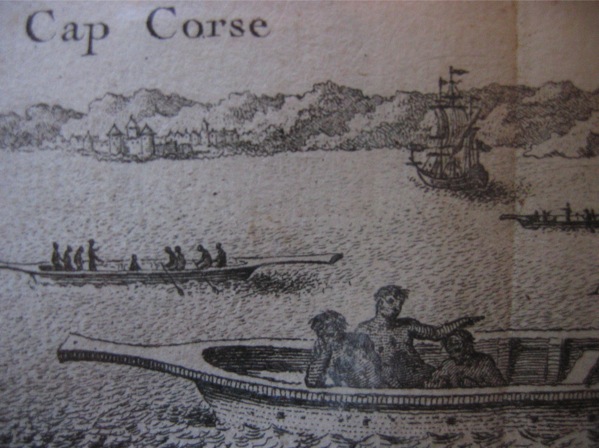

Many eighteenth-century specialists now believe that some of most revealing currents of the Enlightement can be found in Europe’s encounter with (and subsequent representation of) foreign lands and/or non-European people. Not surprisingly, this conviction has generated numerous studies on the status of various “Others” within Enlightenment thought. This is increasingly becoming the case for the various ethnicities of Black or Sub-Saharan Africa, especially those groups singled out as particularly outlandish or “other,” such as the Khoikhoi in South Africa or the semi-mythological group of anthropophagic warriors known as the Jaga in Angola.

The attention that the European representation of Africa and Africans has received is hardly surprising. In my book, I hope to make clear that the Enlightenment era’s view of Africa – and the black African himself (or herself) – are at the crossroads of a series of overlapping and seemingly irreconcilable Enlightenment preoccupations. Coming into focus against the financial, geopolitical, and scientific competition taking place among European powers in the early modern and Enlightenment eras, the representation of Africa and its peoples serves as a junction point for a series of evolving concerns ranging from the biological conception of humankind to the possibility of universal moral values.

© Andrew Curran